Reality Check: The Best Available Bionic Arms Are Still Just Barely Usable

TL;DR We’re making steady progress on bionic arms, but people seem to vastly overestimate the capabilities and performance of current devices. The really futuristic ones are still far, far away.

A note on bias: I’m speaking as a congenital transradial (below the elbow) amputee. YMMV for amputations at different levels. Also, I use the term ‘bionics’ throughout to describe myoelectric arms–this is to match popular parlance.

Whenever I post a video of me training with my bionic arm (more specifically, my myoelectric prosthesis), I always get some variation of the same remarks in the comments section:

It’s so amazing that bionics have come so far from those creepy hook hands. We’re living in the future!

Which is more effective at this point, your real hand or your bionic one? What tasks do you still use your real hand for, if any?

You control it with your brain, right? I saw that on TV!

I’m so jealous. I’d totally replace one of my arms with a bionic one. Soon!

Don’t get me wrong–I’m excited for the future, too. I’m an amputee, and I work on open-source bionics, so I’m clearly pretty invested in the progression of the technology. And it has progressed a decent amount, incrementally, in the last few decades. But tech enthusiasts are quick to get defensive when I try to bring us back to Earth.

I want to state here, for the record:

For amputees like me, even the best commercially available bionic limbs are barely usable for real day-to-day wear, and almost half of all users end up rejecting them.

We’ve made a lot of advancements since I put on my first myo device twenty-five years ago, but we’re not anywhere close to a hand that is anything better than a crude, clunky approximation of a human limb.

The hand I use currently is much better than anything I’ve used before–in fact, I consider mine to be the best you can possibly get today. I also consider myself to be a fairly skilled user, and I still go without mine most of the day–it’s too much of a hindrance.

I think overestimation of modern bionics’ capabilities comes from a few different places:

- The dramatic cosmetic overhaul of myoelectric arms that “disguised” (not necessarily on purpose) what is actually very incremental progress in the underlying tech

- Over-hype of experimental results in science journalism (definitely on purpose)

- Underestimation of amputees’ function without prostheses

But so what, right? People like sci-fi tech and like to stretch reality a little bit. Problem is, I think it’s pretty likely the misinformation about these devices is discouraging amputees who come into this with completely unrealistic expectations about what it’s like to pilot one. Bit strange that the pop-culture fascination with artificial arms steamrolled right over the people they’re actually made for, and stranger still that no one can comprehend an amputee not needing or even wanting one given their limitations.

Myoelectric prostheses’ “Cyberpunk Makeover” is mostly surface-level

Very few people will ever actually operate a bionic arm–looking at photos and posts online is as close as they’ll ever get to one. And man, did myoelectric hands and arms suddenly jump to 2077 in terms of appearance. When I first used one in the mid-nineties, they looked like this:

Image credit - sciencemuseumgroup.co.uk

The design hadn’t changed since 1980. Two sEMG sensors informed a big claw wrapped in a not-quite-your-skin-color glove that opened and closed. I would categorize these as “completely unusable in any real capacity.”

I always hated using mine as a toddler, and I eventually I ditched it and didn’t look back for around fifteen years. When I checked back in, everything was different. Gone were the uncanny-valley fleshy colors and rubbery gloves of old, replaced by slick carbon fiber wraps and composite hands with buttons, LEDs, and accompanying smartphone apps.

We had decided it was cool to be “part robot” and embraced black and chrome. And at some point, we started calling all powered prostheses “bionics”, which is sexier, even though this (admittedly less-than-technical) term looks like it used to only really apply to osseointegrated (i.e. surgically implanted) devices or implanted neural interfaces 1.

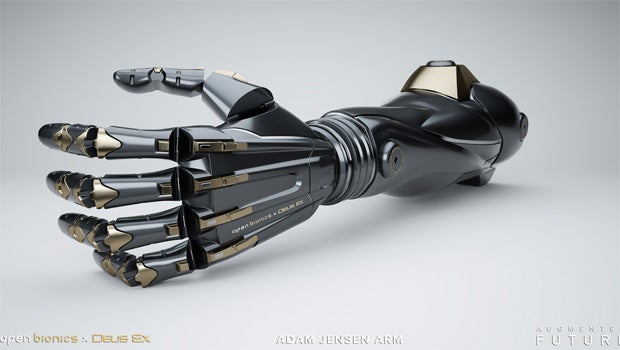

Some companies, like Open Bionics, have made a name for themselves by leaning fully into the aesthetic nature of the devices and developing 3D-printed arms modeled after video game and movie characters:

Image credit - Augmented Future

Of course, many of these changes aren’t just for show. Carbon fiber is stronger and lighter than older composite materials, and the blinky lights and cute beeps do indicate different modes and settings. And hey, Bluetooth connectivity! These are certainly non-trivial improvements in terms of product design.

But underlying it all, the fundamental technology in new myoelectric “bionic” arms is usually the exact same as that of the older prostheses–a single or dual-site sEMG sensor that tells the hand to open and close (unless you’re using a pattern recognition system, like COAPT Control, which I do, but most don’t). The chips are smaller, the sensors a bit better tuned, and the actuators higher quality, but once again, those are incremental improvements. Most importantly, these differences don’t change the answer to the fundamental question:

Will amputees put them on, use them, and keep using them?

The answer is still “No” more often than you’d think. Up to 38% of upper-extremity amputees (UEAs) end up rejecting their prosthetic devices2. That number is for all types of devices across all amputation levels, so maybe the new new devices have improved things, right?

No. The rejection rate for new bionics is actually higher than the average–44% of all device recipients give up and stop using them3.

How could this be? In some more detail:

Bionic arms are less functional than simple cable-driven systems

Yes, you read that right. People don’t believe this one since we’re all so focused on the future. But in terms of weight, reliability, feedback, and function (not to mention cost), almost nothing beats the trusty body-powered system, driven by what is basically a bicycle brake cable.

I blame a lot of the misinformation on the way “inspiring” tech articles frame the different types of prosthetics as a purely linear progression of form and function. They always lay it out the same way:

- The past - Dark days. We used to use crude hooks with no electronics.

- The present - We’re living in exciting times! electronic arms are here, and we can ditch the hooks, thank God. Amputees can finally start living, and look how we’re changing the lives of children!

- The future - Implants and brain interfaces and you can replace your healthy arm for a bionic one, too!

But in reality:

Advanced bionics keep losing to body-powered prostheses in competitions

Ever heard of the Cybathlon? It’s a pretty new competition, a sorta part-athletics-event-part-tech-expo, with races in categories ranging from powered wheelchairs to exoskeletons to brain-computer interfaces to–you guessed it–prosthetic arms.

Any type of prosthesis, bionic or otherwise, is allowed. And in 2016, with dozens of teams competing with the newest bionic arms from all over the world, the decisive winner was a man wielding a simple body-powered hook4.

Image credit - TRS News

And in case you were thinking it was a fluke, the same thing happened in 2020: a 3D-printed, cable-driven arm (Maker Hand, if you’re interested) smoked the competition by 58 seconds. His total race time was ~5:30, to give you an idea of his lead:

The most frustrating thing is, even if you were aware of the event and read the news coverage, you probably wouldn’t have noticed this. The BBC article about Cybathlon 2016 first completely mischaracterizes the contestants as all using robotic arms, because that’s what’s interesting:

Arm amputees used robotic prosthetic arms featuring hands in all shapes and sizes.

then completely glosses over the upset in the results and proceeds to simply grab a quote about the “next step” in bionics technology:

“The next challenge is the touch sensitive nature of the fingers,” said Martin Wallace, development manager for Steeper, one of the companies producing robotic hands.

Maybe the actual next step would be to examine how their robotic arm lost to some printed plastic parts and a brake cable worth around $50.

Any news or tech journalism that features prosthetics is, first and foremost, meant to “inspire” non-amputees and make them feel hopeful for the future. But if rule #1 is “be inspirational”, you can’t really have honest coverage of prosthetics, can you?

Real bionics usage is clumsier than you’d expect

Did you ever notice that it’s tough to find video footage of people performing anything but the most basic tasks with their bionic arms? The internet is full to the brim of prosthetics “inspiration porn”: bionics unboxing experiences, delighted faces (often of children for extra emotional appeal), and quick demos of something as trivial as picking up a ball or cup and putting it back down. Maybe they don’t even pick up anything–they’ll just open and close the hand a few times.

To me, the reason why is pretty simple–bionics still have quite a bit of trouble doing anything more than the simple stuff.

The Grablab at Yale finally went out and collected hours of video footage of bionics users performing real, everyday tasks, outside of a lab setting. And the results aren’t pretty:

As elaborated on in the accompanying paper5, they found that:

- Myoelectric arms only got used for 19% of daily activities. By comparison, simple body-powered devices were used 28% of the time. By that metric, bionic arms spend more time as dead weight.

- When the myo arms were used, only 30% of the object manipulations users performed were prehensile (as in, opening and closing their devices around objects as they’re designed to do). Much more frequently, they nudge and push objects with their closed hands or hooks, hang things off the arm, or wedge them between arm and trunk. That means for 70% of the usage of bionic arms, the advanced multi-articulating hands and accompanying control systems are completely superfluous. You can see their hesitation when trying to perform prehensile manipulations–they don’t actually trust the devices.

Twenty-three grips, and still nothing to watch

One of the biggest mechanical advancements made with new myoelectric hands is a steep ramp-up in the complexity of their articulation. Instead of a single open-close grip, modern multi-articulating hands often have a dozen or more pre-set grips representing different hand positions. My TASKA hand has 23, ranging from pincer to tripod to handshake to sphere grip to “silly” ones like the heavy metal horns.

What this actually means is: instead of simply failing to pick up an irregularly shaped object, I can now fail to pick it up a bunch of different ways! More grips don’t really translate into improved function, and I’ve only found two or three of them to be useful.

Myoelectrics aren’t really “mind controlled” the way you think

Sure, you can call them that, but then everything you do is mind-controlled, isn’t it? If I place a quarter on my arm, and twitch my bicep until it slides off, did I move the quarter with my mind? Not really. Myoelectrics are muscle-controlled.

Muscles are mind-controlled, and you have to move an existing part of your body, i.e. twitch the muscle under the sensor, for the arm to activate. Really they’re just listening to voltage changes that your body movement creates. It may seem like I’m splitting hairs, but to me it seems like a pretty meaningful difference. That intermediate step, coupled with the sensor placement on the skin outside the body, introduces a huge amount of noise.

Yet journalists love to conflate the two. In a Healthline article about a true neural interface, the author writes this about myoelectrics:

Prsic says like the new mind-controlled osseointegrated limbs, the myoelectric prosthesis is more or less also mind-controlled. The brain sends an electrical signal to the nerves and muscles, which is then transferred to the prosthesis.

In their popular video 5 Futuristic Mind-Controlled Prosthetics, Tech Vision lumps the Open Bionics Hero Arm, a simple myoelectric hand, in the same category as brain implants and neural interfaces, saying it gives the user an “unrivaled lifelike sensation.” In addition to being a complete mischaracterization of decades-old, clunky EMG tech, the statement also implies the existence of transferring touch or feeling to the user (which, of course, it doesn’t). In reality the only novel thing about the Hero Arm is that it’s 3D-printed.

Even the Atom Limb, based on IP6 from the DARPA-funded LUKE/DEKA arm (which is undoubtedly a huge step forward), boasts “mind control” in its literature, with the tagline “Just think and it moves”7. Yet they also mention there are no implants, and they recommend an outpatient functional enhancement surgery to ensure signal fidelity. That surgery is almost certainly TMR, meant to improve myoelectric control in amputees, meaning this is also probably a myoelectric device, just with higher resolution.

Experimental prostheses’ level of function should be treated skeptically until they are widespread

I’m not saying neural interfaces aren’t the future of the technology–they probably are. But the awesome mind-controlled prosthetics you see on the news aren’t even close to available. I wouldn’t blame you if you thought otherwise: in a report on three (3) Swedish patients trying out the e-OPRA neural-interfacing arm, Science Daily thought an appropriate headline was Mind-controlled arm prostheses that ‘feel’ are now a part of everyday life.

Here’s some footage of arms that use a new type of neural interface, based on signal amplification from grafted muscle, out of the University of Michigan that boasts intuitive, finger-level control:

The users say the hand is great, and I believe them. At the same time, the “intuitive, finger-level control” isn’t really on display in this video–they demo a few different types of grips that I could perform just as well with my myoelectric hand. The scientific community obviously wouldn’t let them fabricate their results, so I do believe the technology allows for finger-level control. This is probably a result of the users having limited time to try the device. Still, why get hyped before you see it proven?

The absolute best demos I’ve seen have been those from the Modular Prosthetic Limb out of Johns Hopkins, which would make sense given the project’s $120MM price tag. Even though the finger movements aren’t very precise, what’s most compelling here is the sheer number of degrees of freedom (DOF) on display, since the user is missing hand, wrist, elbow, and shoulder. Controlling all of that requires 26 DOF:

And this is without the user even being allowed to take the arms home to practice! However, the MPL is a research platform, and in the video, a researcher mentions they need to reduce the cost 10x and go through several more years of hoops to make things commercially feasible (though the video is seven years old by now).

When these types of arms first release commercially, they aren’t necessarily going to be orders of magnitude more functional than what we have now, even if long-term they will certainly have the most potential. There’s a long road ahead.

Remember the Cybathlon I mentioned earlier? Two of the contestants were using the e-OPRA system, a revolutionary, history-making, Earth-shattering two-way neural interface with implanted electrodes that also transmit the feeling of touch to the user. Everyone agrees: this is truly a whole new totally unprecedented level of prosthetic control.

So how’d they do? They finished in 3rd and 6th, losing to the $50 hand with the brake cable8. Surely their experience with their new limbs is much more intuitive, but just how much does that matter if it doesn’t translate to being able to use it more effectively?

(That’s an open question for discussion. For acquired amputees who lost their limbs later in life, it probably matters a lot. For congenital amputees like me who never had a hand, it doesn’t really matter at all.)

“Something” isn’t better than “nothing”

At this point in the piece, I expect a question like:

Okay, so the awesome mind-controlled devices aren’t ready yet. Even if the myoelectric hands aren’t perfect, at least they’re something. How else are you going to live a normal life?

But we’re not comparing against zero here. Transradial amputees like myself have a very high level of function that basically approaches that of a two-handed person. So actually, the threshold for being “better than no prosthesis” is super high.

As an example, with no prosthesis on I can type >100 word per minute:

But with one on, I can hardly type at all. It makes sense–typing requires a high degree of speed and dexterity, which is exactly what bionics are bad at. But if you work an office job and are at the keyboard all day, then in the evenings blow off steam by, say, playing video games (using a game controller requires similar dexterity), then when exactly are you going to wear the hand?

People have this idea that amputees need to be “fixed” with technology so they can live a “normal life”. This sentiment has been cultivated by years of style media coverage where a “helpless” child loses their arm but is “saved” by technology. The term “changing lives” is always attached. But my life has never been changed by a prosthesis, and we’re already thriving the way we are. Prosthetic arms are going to have to get really, really good to meaningfully improve our function, and that’s probably a few decades away.

Sky-high Expectations are Scaring off Potential Bionics Users

Here’s why any of this matters. If you’re an amputee these days, there’s overwhelming pressure to have a sick-nasty bionic limb and be a “cyborg”. And if you don’t have one, it must be because you’re waiting for insurance to approve one, right? After all, “it’s amazing what they can do now.”

So you go to the doctor and shell out thousands of dollars, which may be completely straining your finances, but it’s worth it because you’re getting a new bionic arm, and it’s mind controlled! And then it finally arrives, and you feel more disabled wearing it than before you had it. It can’t really pick things up like you thought, and your arm, which used to pick things up just fine with no hand, is now stuffed inside a socket where it can’t feel or do much of anything.

Eventually, the bionic device ends up in the closet and collects dust, which isn’t very cool or Cyberpunk at all. Then you have to face everyone to whom you excitedly mentioned the new arm and tell them that it doesn’t actually work that well, but they’re consuming all the same bionics hype content as you and still believe we’re in the future, so to them you must not be using it right, or you just gave up.

I’m not the only one who thinks this. Though these takes are rarely published, I found one really good article (“I have one of the most advanced prosthetic arms in the world–and I hate it”, Input Magazine) that spells out all my same frustrations. There’s also a really good write-up from 99% Invisible about it.

I’ve also made other videos talking about this in greater detail:

Anecdotally, though, the sentiment among upper-extremity amputees isn’t rare at all. Almost every UEA I know has expressed annoyance at myoelectric arms and ambivalence regarding the explosion of hype surround Cyborg Chic and bionics.

“But you use a bionic arm!”

I just spent a long time talking about why today’s bionic arms aren’t that good. But I do own one, though I don’t wear it that often, and I make lots of content explaining how it works to people. Am I a big hypocrite?

Well, maybe. But I justify my role here a few ways:

- Bionics need device pilots - if people don’t wear them and provide feedback, we’re going nowhere fast. How are we supposed to tell what’s impossible with current technology vs what’s just difficult? Who’s writing the guide book for intermediate and advanced bionics usage? As an amputee and a wearable robotics engineer, I’m a pretty good spot to work with the engineering teams behind hands and control systems.

- Legitimate use cases do come up - usually they involve situations where I need to hold multiple things, and pinning them against my body like I normally would doesn’t cut it. Two I’ve noticed have been at buffet style restaurants (the bane of an amputee’s existence), where you need to balance plates and glasses or risk spilling food everywhere, and at the airport where dragging my luggage too close to my body makes it bounce off my feet every time I step. It may seem indulgent to have a bionic arm for such niche uses, but also:

- My insurance covered it - so what the heck?

I try to perform real, deliberate practice with the arm every day or every couple days. But the vast majority of the time, I’m all natural. When easily available bionic devices can actually deliver a significant increase in my function, maybe I’ll switch things up.

-N